Beyond survival: Strengthening women-led mental health interventions within tribal communities in the Indian Sundarbans

BY SHABERI DAS • March 16, 2025

In the Indian Sundarbans, where land and water are in constant negotiation, resilience is about more than just survival – it is about adaptation, endurance, and the quiet work of rebuilding lives, again and again. Here, climate change is relentless, embedded in daily anxieties about eroding riverbanks, uncertain monsoons, and storms that undo years of meticulous planning in a single night. The crisis unfolds at multiple levels: in the rising waters that swallow homes and fields, in the loss of familiar landscapes, and in the silent, internal erosion of mental well-being.

Yet, mental health remains a footnote in climate adaptation discussions, overshadowed by economic and infrastructural concerns. Women, in particular, carry this burden in ways that remain largely invisible. As men migrate for work, women bear the full weight of household responsibilities, unpaid care work, and resource management. During lean periods, they eat smaller portions or skip meals to ensure others at home are fed. After disasters, they salvage what remains, stretch dwindling resources, and worry endlessly about their children’s futures. Despite this, their health and well-being is rarely framed as a climate resilience issue.

The Mon-Majhi initiative, part of the Sound of Silence project, disrupts this oversight. The Bengali term ‘mon’ means mind, and ‘majhi’ boatman, capturing the role of community mental health facilitators who guide others through emotional challenges, much like a boatman navigating the river. Embedding psychosocial support into climate adaptation efforts, the initiative recognizes a critical yet underexplored reality: mental well-being and emotional resilience are fundamental to climate adaptation.

This article examines how the Mon-Majhi model of community-led mental health intervention offers a blueprint for integrating eco-psychology, gendered resilience, and climate adaptation within rural and marginalized communities – and why failing to do so will leave the most vulnerable even further behind.

The overlooked crisis: Women, climate change, and mental health

Discussions on climate change often stop at economic loss and damage – diminished crop yields, loss of fisheries, and migration pressures. But what does it mean to experience climate change at a psychological level?

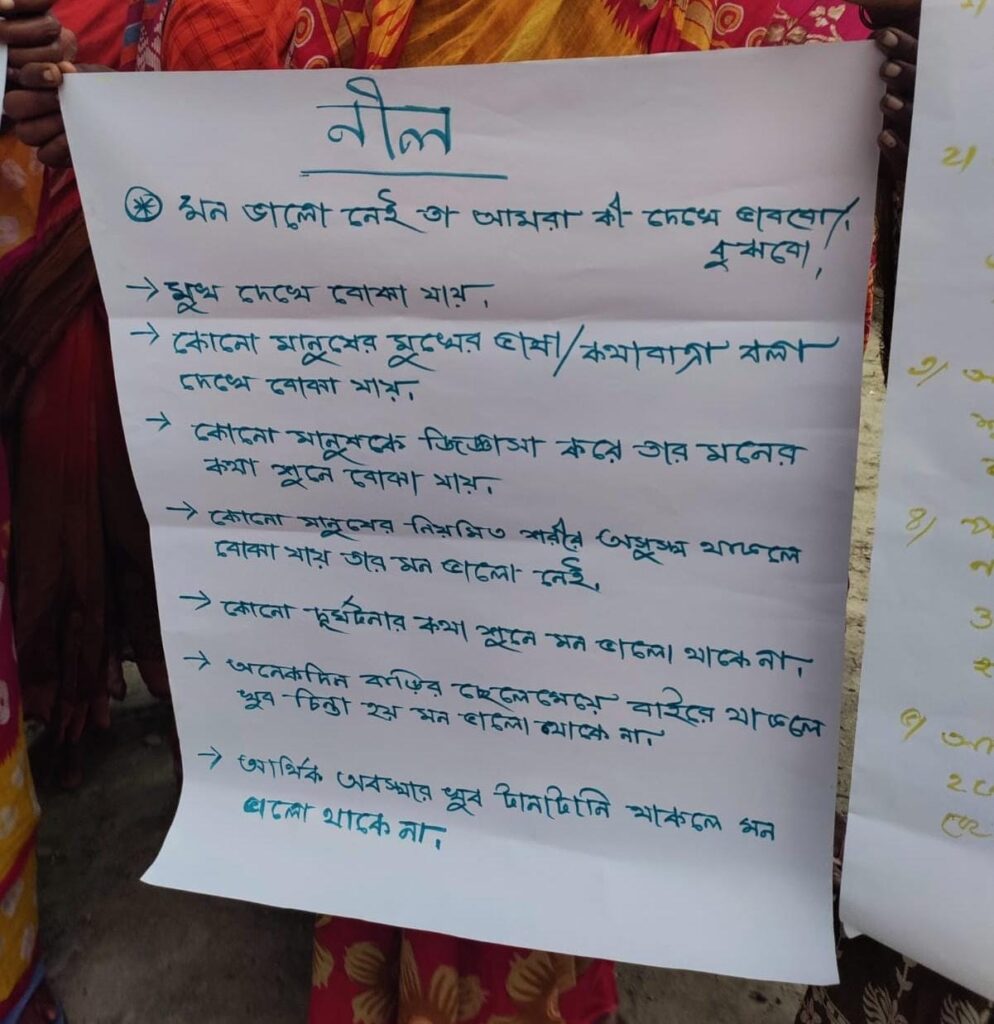

For women in the Sundarbans, climate change is an everyday anxiety that shapes how they plan their lives, make decisions, and process loss. Their concerns are multi-faceted:

- Economic stress: Late rains or storm surges destroy crops and fisheries, leaving families without food or income.

- Fear of displacement: Erosion and cyclones force families to abandon homes and rebuild elsewhere with little support.

- Post-disaster fatigue: After days in overcrowded shelters with little food, clean water, or sanitation, people return to rebuild, with the lion’s, often without for formal support. The lions’ share of rebuilding efforts alongside balancing domestic chores and other responsibilities falls on women.

- Uncertainty of migration: Husbands leave for distant cities in search of work, leaving women to manage homes and finances alone, often with irregular remittances.

- Exposure to violence: Social isolation and economic strain contribute to substance abuse and domestic violence against women and children, exacerbating their mental distress.

Moreover, mental health is still stigmatized, especially within rural communities. Stress, anxiety, and trauma are seen as personal struggles, not systemic challenges linked to climate instability. Women have few outlets to discuss their fears, making distress an isolating experience.

The worst affected by these challenges are women from marginalized tribal communities, some classified as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs). Many of these communities lack official identification, own little land, and live in temporary shelters along island fringes. Their livelihoods are increasingly precarious, their cultural heritage is rapidly disappearing, and they face some of the highest levels of multidimensional poverty in the region.

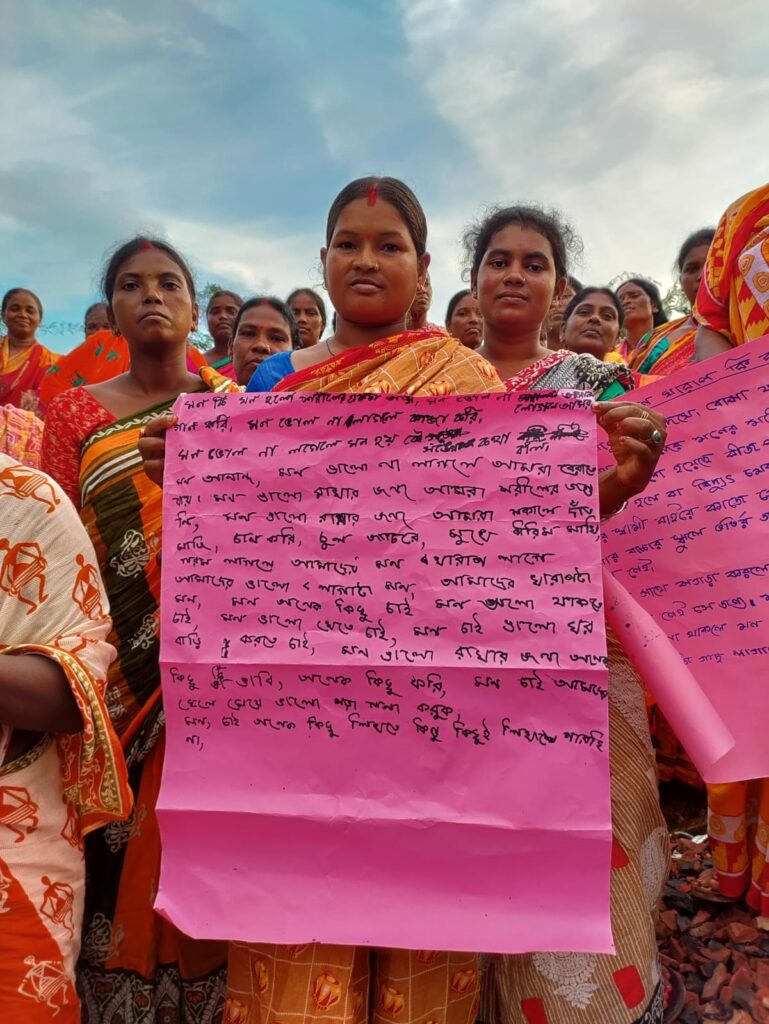

To better understand these challenges, we conducted a mental health survey to assess the issues faced by women in these communities and to determine whether the presence of psychosocial support volunteers (Mon-Majhis) would be helpful. Women responded in the affirmative, highlighting concerns detailed in this article. Their responses reaffirmed that accessible, community-led mental health support is not just necessary but urgent.

This is where Mon-Majhi’s approach becomes critical. By creating spaces for women to discuss their emotions and acknowledge shared distress, it normalizes mental health conversations in a practical, culturally relevant way. Informed by eco-psychology, which emphasizes the deep connection between human well-being and the environment, Mon-Majhi helps women understand their loss of place identity and sense of security in the context of ecological disruptions. The initiative proves that mental resilience is not an afterthought in climate adaptation – it is a precondition for survival.

The Mon-Majhi model: Key components and emphases

Serving those who usually slip through the cracks of formal mental health infrastructure, Mon-Majhi embeds mental health support within existing community structures in vulnerable rural places to provide mental health first aid and identify those in need of formal care. The initiative is effective and replicable because it focuses on:

1. Breaking the mental health stigma

Rather than treating mental health as only a specialist issue requiring external intervention, Mon-Majhi trains women within the community to provide psychosocial support. These informal facilitators learn to recognize trauma, offer peer support, and lead mental health discussions, reducing the stigma. When mental health support comes from within the community, it is easier to trust, access, and sustain, making mental health a shared concern rather than an alienating force.

2. Leveraging community structures as healing spaces

Mon-Majhi taps into existing women’s self-help groups (SHGs) and collectives to introduce mental health discussions. Women already gather to discuss farming and finances – these groups now also offer psychosocial support, validating each other’s experiences and reducing the isolation that often comes with anxiety and distress. Trained Mon-Majhi volunteers create an informal safety net for women in crisis, ensuring support at the grassroots level.

3. Connecting mental health to climate realities

Unlike conventional mental health programs, where discussions feel abstract or detached from daily life, Mon-Majhi links psychological well-being directly to environmental change. The awareness and training sessions encouraged women to talk about mental well-being and reflect on how climate disruptions affect their sense of security and stability, using familiar language, culturally-relevant metaphors and collective wisdom. Discussions highlighted how the mind (“mon”) responds to disasters and environmental degradation, allowing distress to be seen as a shared experience rather than an individual weakness. This eco-psychological approach helps women articulate their emotions without feeling as though they are speaking about something unnatural or foreign, thus firmly grounding the initiative in their lived realities, and making it sustainable.

Scaling up Mon-Majhi: Future directions

The success of Mon-Majhi raises a crucial question: How can similar models be expanded and integrated into broader climate resilience efforts?

1. Recognizing mental health as a core climate adaptation strategy

Climate adaptation policies cannot afford to ignore mental health. Just as disaster preparedness includes evacuation plans and infrastructure reinforcements, it must also include psychosocial support. Women should be trained not just in disaster response logistics but also in managing trauma, stress, and anxiety. Additionally, government programs and NGOs must support and formalize community-based mental health networks, just as they support economic resilience and sustainable development.

2. Expanding community group networks

Community groups such as SHGs have proven effective for collective action. Embedding psychosocial support within such groups is a low-cost, scalable way to expand interventions. More women’s groups can be trained as community mental health facilitators, ensuring every village has accessible, peer-led support.

Mental health discussions can be integrated into group activities, making psychological support more accessible and reducing stigma.

3. Institutionalizing an eco-psychological approach

For communities where the environment is central to both livelihood and identity, mental health interventions must acknowledge the deep ties between ecology and well-being. Climate adaptation programs should recognize solastalgia or ecological grief as a legitimate concern and integrate emotional well-being into sustainability planning.

4. Supporting children and youth

By extending mental health support across generations, mental health initiatives can foster a more emotionally aware and resilient future. Young people are often the first to witness the emotional struggles of their mothers, siblings, and peers, and also become victims of domestic violence. Yet they rarely have the knowledge or confidence to offer support. Hence, equipping youth with basic emotional well-being training can help them recognize distress in their families and communities, offer support, and encourage open conversations. Integrating active listening, stress management and peer support into existing youth programs can create a culture where mental health is understood as a shared responsibility.

The idea that mental health is separate from climate adaptation is a false distinction. Women in the Sundarbans do not experience climate change as purely external – it shapes their emotions, stress levels, and sense of possibility. Mon-Majhi proves that community-led mental health interventions are not only possible but essential. Scaling up this model is not just about expanding a program; it is about redefining what resilience truly means.